Legendary Coach Ed Temple "Changed the Landscape of Women's Track Forever"

Legendary Coach Ed Temple "Changed the Landscape of Women's Track Forever"

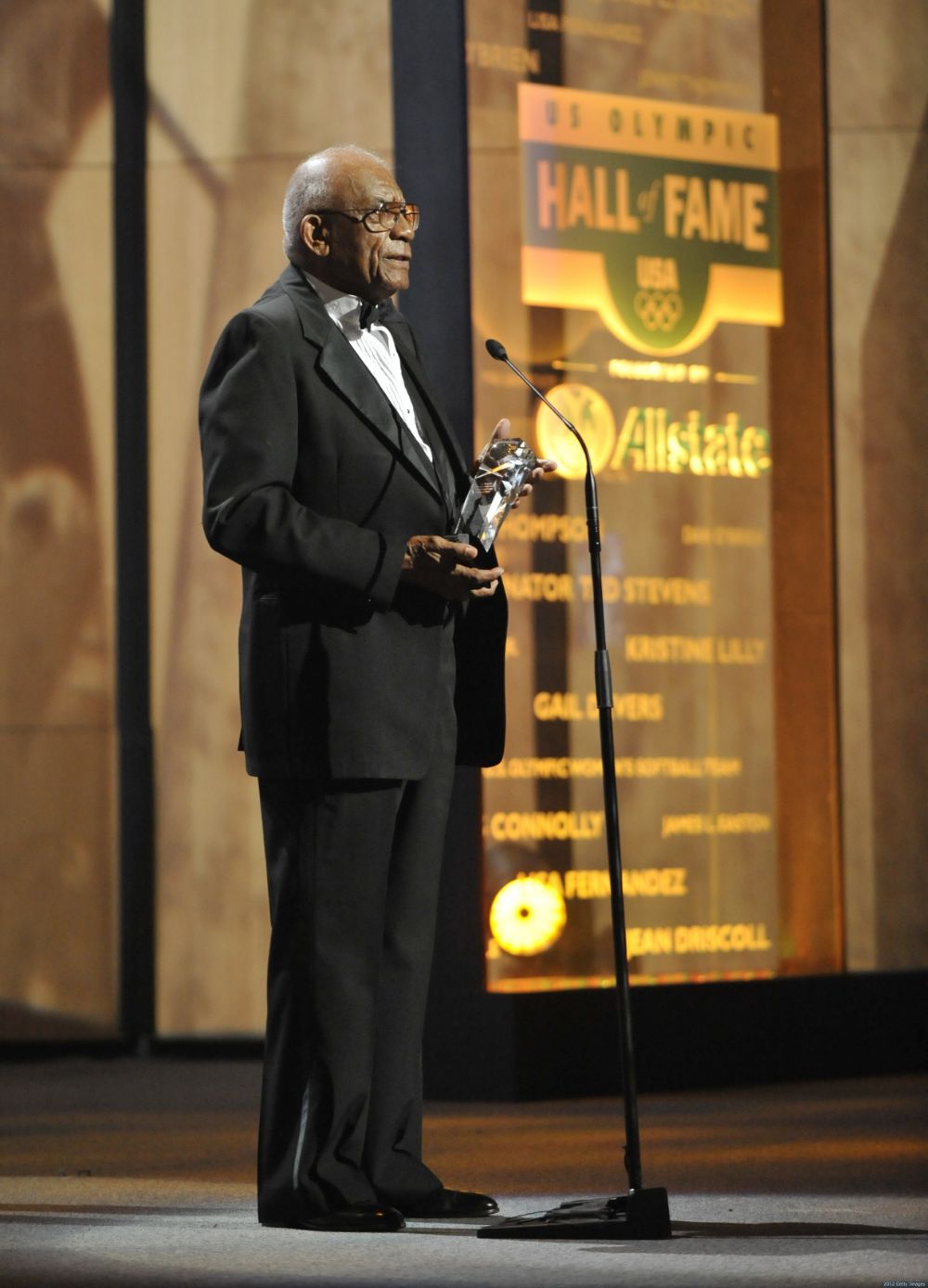

Legendary track and field coach Ed Temple’s impact on the sport will be discussed for generations to come, say those close to the man who led Tennessee State University’s famed Tigerbelles to 23 Olympic medals.

Temple died Sept. 22 at the age of 89. A memorial service is planned for Sept. 30 in TSU’s Kean Hall.

“His accomplishments are unparalleled and continue to resonate even today on our campus and with any organization participating in the sport,” said TSU President Glenda Glover. “Tennessee State will always remember Ed Temple, the man and the coach.”

Davidson County Criminal Court clerk Howard Gentry, Jr., who was TSU’s athletic director when Temple retired, called him “an icon, not to be duplicated in any form.”

“He built a team of world class track participants who changed the landscape of women’s track forever,” Gentry said.

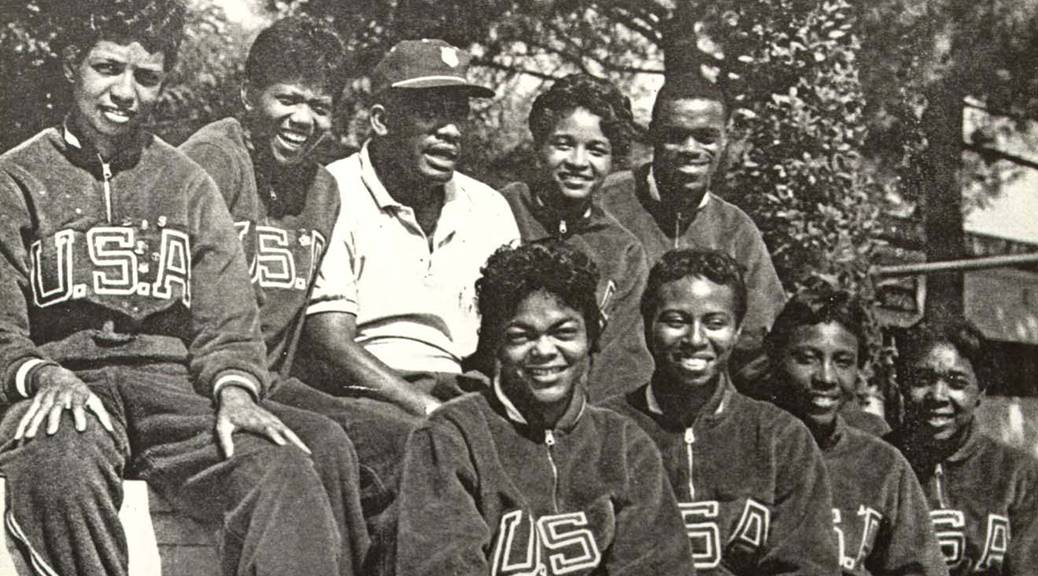

Temple was head of TSU’s women’s track and field program from 1950 to 1994. He led more than 40 athletes to the Olympics, snagging 16 gold medals. His athletes also accumulated more than 30 national titles.

Dwight Lewis, who is co-authoring a book about the Tigerbelles, said there were a few countries like Germany that dominated track and field, particularly at the Olympic Games, up until the mid-1950s. But then the Tigerbelles made their presence known at the Games in Melbourne, Australia, in 1956 when they won several bronze medals.

They continued that domination at the Olympic Games in Rome in 1960, highlighted by Wilma Rudolph’s three gold medals, the first American woman to win that many gold medals in track and field during a single Olympic Games.

“Since 1960, it’s been America dominating,” Lewis said. “And it was the Tigerbelles who started that wave. Coach Temple would often say, ‘They paved the way for other women in sports.’”

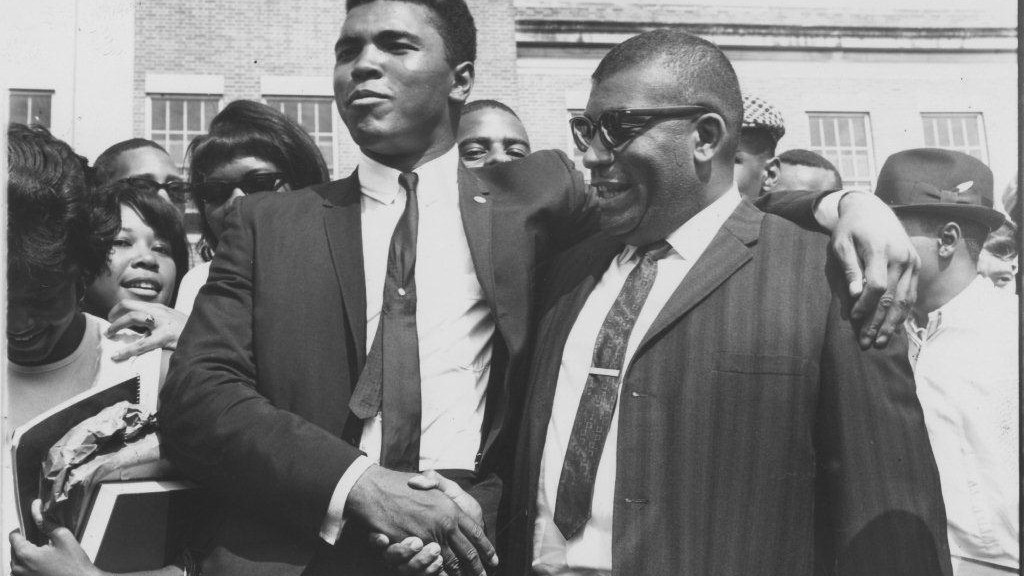

Olympic gold medalist Ralph Boston, who was among the athletes that Temple trained, agreed his legacy lives on.

“He certainly made a difference in the track and field world,” said Boston, who got a gold medal in the long jump competition during the 1960 Olympic Games in Rome.

Boston and others say Temple’s accomplishments were even more impressive coming in the midst of severe racism and discrimination that permeated the United States during the 1950s and 1960s.

“He did it in some of the toughest times that our nation faced,” Gentry said. “And so to see that occur in the 50s and the 60s, and then moving into the 70s, was an amazing feat by one person. But also a true inspiration for all who had the ability to experience it.”

Monica Fawknotson, executive director of the Metro Sports Authority, of which Temple was a founding member, said Temple had a “profound influence.”

“He not only embodied excellence, he expected it from us and, like all great coaches, called it out of us,” Fawknotson said. “He taught us that greatness is not about one’s color or gender, but about hard work and the spirit of a person.”

In 2015, a 9-foot bronze statue was unveiled in Temple’s likeness at First Tennessee Park in Nashville. The visionary for the statue was Nashville businessman Bo Roberts, who said the project had been in the works for well over a decade, and that he was glad the unveiling could finally take place for one of his longtime heroes.

“We hope locals and visitors will come to this statue to learn about and honor one of the city’s most important citizens,” Roberts said.

Coach Temple’s legacy is now on display for the world to see as exhibits in the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. The TSU collection includes Temple’s Olympic jacket, replicas of gold medals, and other artifacts or memorabilia.