- Home >

- North Nashville Heritage Project

- > People

Everyday People

James Harding b. 1842

Born a slave in 1842, James Harding lived with his wife of forty-four years, Sallie, at 1505 Jackson St. in North Nashville. Harding was one of fourteen enslaved African Americans owned by Thomas Harding, a wealthy Nashville planter.

Harding’s brief but very descriptive narrative provides sobering insight into the slave experience in Nashville. Of the Public Square, a space today identified with peace and tranquility amid a bustling urban center, Harding remembers the square as a place where “they would auction off slaves as if they were cattle.” As a carpenter working on the construction of Fisk University’s Jubilee Hall, Harding remembers receiving notices from the Ku Klux Klan of their intent to burn down the dormitory.

Take a moment to consider his narrative, posted in the January 31, 1918, edition of the Nashville Globe.

- James Harding Interview-Nashville Globe, January 31, 1918.

- Thomas Harding 1860 Federal Census-Slave Schedule

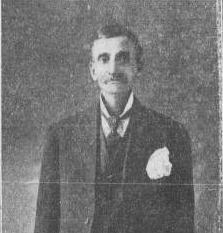

George B. Hall

1616 Jackson Street

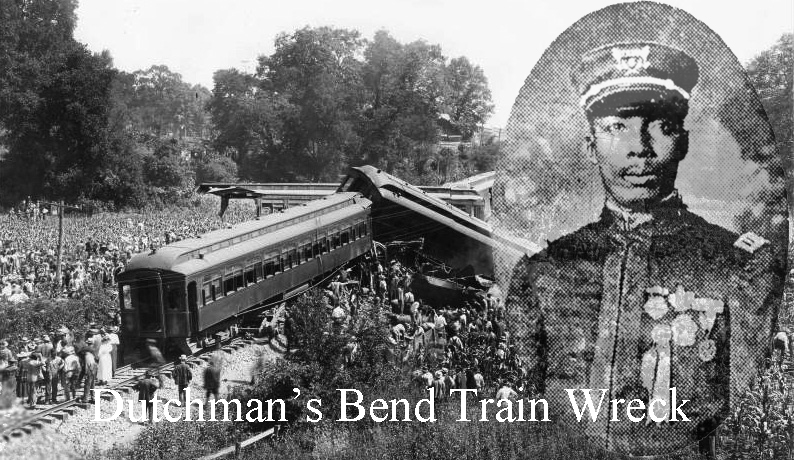

Dutchman's Bend Train Wreck

Meet George Hall. Born in 1870, George Hall became a well-respected member of North Nashville’s African American community. Born five years after the end of the Civil War, by the turn of the century Hall seemed to serve as an example of the success possible for hard working African Americans in Nashville. Nashville was a city very much committed to keeping blacks in subordinate positions, yet some obtained a decent standard of living. A remarkable feat when one considers the ever-present racism that confronted them in every aspect of their lives.

Married at the age of twenty-three, Hall and his wife Lizzie immediately set out to create a home and family, with their first child, Milrie, being born a year after their wedding. She would be the first of five children. Meek, George, Jr., Arma, and Alberta would follow as the family entered the twentieth century. Lizzie and George never received a formal education, but they could both read and write and made certain that their children, members of the first generation of African Americans to live without fear of enslavement, could as well.

Much of Hall's success can be traced to his finding employment as a porter on the Nashville, Chattanooga, and St. Louis Railway. Photographs of Hall reveal a very distinguished and proud man, but his job as a porter would require him to face many insults and indignities as an underpaid, overworked laborer. The real money on the trains came in the form of tips, and tips came as a result of smiles; miles and miles of smiles. A position as a porter was a good job for African Americans at the turn of the century, providing a way for many of them to enter the black middle class.

George Hall died on July 9, 1918, shortly after 7 o’clock in the morning when the NC&St.L No. 4 train collided with its No. 1 train at Dutchman’s Bend (near present day Belle Meade). Both trains, travelling at speeds of at least 60 mph, shattered the calm of the Tuesday morning, setting the adjacent cornfields ablaze. By the time the smoke cleared, Hall’s body lay among the 151 passengers found among the wreckage. According to the of casualties listed in the Nashville Globe, fifty-seven African Americans, many who were on their way to work at the munitions plant located in Old Hickory, TN, lost their lives that fateful morning.

Hattie Hodgkins Hale

Hattie Hodgkins Hale

711 Gay Street

Hattie Ewing Hodgkins was born in Nashville on December 15, 1891. Like many of the babies born in the city on that day, her parents welcomed her into the world at their home. Her birth marked the second time her father, Nashville attorney and public notary William Hodgkins, had received word that his wife had given birth to a baby girl.

Hodgkins quickly made a name for herself as an adept pupil, attending the city’s Pearl High School and graduating at the age of sixteen. Having gained a reputation as one of Nashville’s “most brilliant” young ladies, she then matriculated through Fisk University, graduating with honors in 1911. With the opening of Tennessee A&I in 1912, Hodgkins secured employment as a professor and private secretary for the university’s first president, William Jasper Hale.

In October 1913, Hodgkins appeared on the arm of President Hale shortly after the start of a social function being held in the campus’s main building. She, dressed in a gray tailored suit with a large picture hat, marched arm in arm with Hale to the stage before a surprised audience of students and faculty. Then as suddenly as the couple appeared, the sound of the Wedding March filled the auditorium. What many thought would be simple gathering of students and faculty that night unexpectedly became the wedding of Tennessee State University’s first president.

Although her duties as first lady required her to entertain the guests who occasionally visited A&I, Hale was also intimately involved in the Women’s Club movement in Nashville, becoming one of the leaders of the Forward Quest Club. The organization functioned under a belief articulated by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, an idea that argued that the uplift of African Americans could be better accomplished “by the mothers, wives, daughters, and sisters of our race than by the fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons." Consequently, the group sought to engage Nashville’s women in each stage of their development, reaching out to them as girls, adolescents, and young adults.

Their involvement with Nashville's young ladies sought to teach them self-respect, encouraged them to become educated, and to vigorously embrace their role as the caretakers of their homes and communities.

webpage contact:

North Nashville Heritage Project